ILLUSTRATION BY YUNYI DAI / NEXTGENRADIO

The

Impact

of

Climate Change

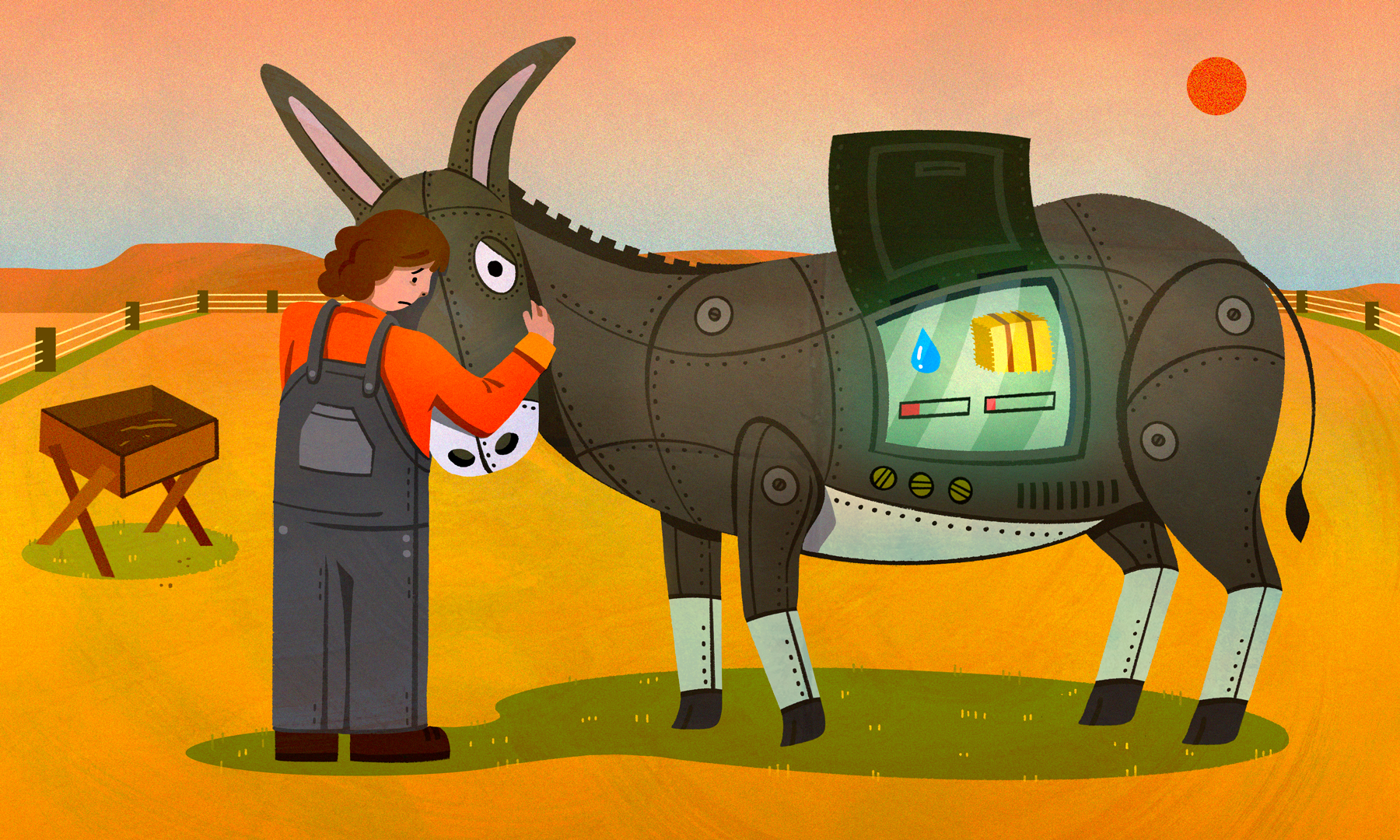

In this project we are highlighting the experiences of people whose lives are being affected by climate change.

Isaac Vargas speaks with Karen Kaehler, a hobby farmer, about her concerns regarding the impact of climate change on her donkeys and horses. Having enough grass to graze is just one of the many issues climate change has presented on her farm. Kaehler, who lives in Strasburg, Colorado, must consider the rising costs of hay and water consumption as drought persists and temperatures rise. She is worried about the future of her four-legged family.

Donkeys and drought: How climate change affects a hobby farmer in Colorado

Donkeys and drought: How climate change affects a hobby farmer in Colorado

Click here for audio transcript

Karen Kaehler: (Sound of donkey bray, kind of a series of honks, with big breaths in and out) When they bray, it’s sort of like a cat purring. It’s just, it’s just their emotions coming out.

Hi, I’m Karen Kaehler. In my professional life, I am a corporate chef for Red Robin restaurants. In my personal life, I have a boarding stable in Strasburg, Colorado. It’s called Chamor Stables. “Chamor” means donkey in Hebrew.

Right now we’re sitting in a barn and it smells like, kind of, maybe, spent grains because they do eat grains. Horse manure really doesn’t smell bad. It’s not a bad smell. It’s a sweet smell.

Sammy is the classic handsome, dark-brown donkey, and he is the most photogenic animal on the property.

I’m rubbing inside her ears. That’s a place she can’t get to and see how she’s lowering her head. She’s, like, very submissive and that just feels super good to her.

(Sound of Kaehler rubbing donkey’s ears)

Every August we get one big delivery of hay that will suffice for the whole year. Last year, these bales cost us about $185 apiece. This year because of the drought, we’re looking at about $250. So that’s one way the climate and the drought has really affected us. You definitely do without other comforts when those kind of expenses happen.

I worry about the future for my animals as far as the climate goes, not just my animals, but all of the animals, you know, throughout the country, really.

In the winter we have an automatic horse waterer. It continually fills up as they drink.But in the summer we supplement it with this 70-gallon Rubbermaid waterer and each day at least 35 gallons have been drunk down. It just gives you an idea how water they do need. These guys really do need shelter. They need clean water sources. And they need grass they can actually graze on. And I do worry about that.

They can go wherever they want. Beyond this fence, which is probably a hundred yards from us, we have another 35 acres in the back. Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of grass to regrow this year, but we do move them from field to field. If there’s so much drought that we’re not getting grazable land, that means we’re gonna have to start supplementing their diets with grain, and we’re gonna have to buy even more hay if they can’t be grazing at home.

Quiet time with the horses and donkeys is, um, it, it’s spiritually and emotionally nurturing. See, I’m starting to tear up.

I’ve had a very, uh, personally challenging couple of years. I just don’t know how I would, how I would’ve coped, uh, if it weren’t for them.

So of course I worry about what their future’s gonna be like in my lifetime and beyond.

Just know that these are noble beasts who have literally built our country and they deserve our attention…and our love.

(Sound of donkey bray)

For livestock in the arid West, drought is a looming disaster. A group of horses and donkeys in eastern Colorado is running out of grass to graze, and for their owners the cost of their hay is going up.

Karen Kaehler of Strasburg first noticed the impact climate change had on her herd when the drought stunted the hay she grows for them.

“That’s when we realized we were not going to be able to self-sustain our animals,” she said. The cost of a bale of hay is now at $250 per bale, up from $185 just a year ago.

Kaehler works as a corporate chef for Red Robin. But in her personal life, she runs a boarding stable known as Chamor Stables. “Chamor” is Hebrew for donkey.

Donkeys that Karen Kaehler adopted, most from a local rescue shelter in Bennett, Colorado, graze one of the fields on her property, Chamor Stables, in Strasburg, Colorado. Kaehler says the amount of grazable land has decreased over the years.

ISAAC VARGAS / NEXTGENRADIO

“I worry about the future of my animals,” she said. “These guys really do need shelter. They need clean water sources. They need grass they can actually graze on…there’s so much drought and that means we’re gonna have to start supplementing their diets with grain and buy even more hay.”

Climate change in Colorado means less forage for Kaehler’s animals, which means greater competition for what’s left between other livestock and wildlife. Kaehler said drought and climate change have made providing enough food, water and shelter difficult. As she described the challenges, Rumble, a large paint horse and the alpha of the group, and Pebbles, a gentle quarter horse, snuck into the hay room and helped themselves to seconds.

“They know where the good hay is,” Karen’s husband, Brian Kaehler, said. He’s a native Coloradan and works as a mechanic for United Airlines.

The Kaehlers’ barn, which is decorated in colorful wooden plaques of each animal they’ve cared for over the years, smells like horse manure, grassy and grainy.

“It doesn’t smell bad,” Kaehler said, “It’s sweet.”

Karen Kaehler feeds Rumble the horse and Cassie the donkey at Chamor Stables. Kaehler regularly doles out treats by hand to each of the equine animals on her farm.

ISAAC VARGAS / NEXTGENRADIO

She moved like a mother navigating her kids’ playroom as she gave a tour of her farm. Surrounded by curious horses, donkeys, dogs and Charlie the barn cat, Kaehler talked about how her horse, Samson, developed skin cancer on “his carrot,” referring to his genitalia.

Equines run the risk of skin cancer resulting from extreme sun exposure. Since donkeys are desert animals, winter weather shelter has been the priority for donkey owners. However, Kaehler began thinking about ways to provide shade for her animals in the summer due to rising temperatures caused by climate change.

She and her husband built an indoor horse riding arena in 2020. As a professional chef, Kaehler said people are taken aback when they see the simple kitchen in her home. She chuckled and recounted her mother-in-law telling her: “You know, dear, I probably would’ve redone the kitchen before I built an indoor riding arena.”

Rumble, left, and Pebbles, take shelter in the barn at Chamor Stables on an August day. Above them are wooden plaques for all of the equine that Karen and Brian Kaehler have cared for over the years.

ISAAC VARGAS / NEXTGENRADIO

While working around her farm in Strasburg, Colorado, Karen Kaehler wears a Chamor Stables hat she designed. Kaehler’s whimsical drawings of donkeys also illustrate “Ears To You,” a picture book published by Longhopes Donkey Shelter to raise funds to help at-risk donkeys.

ISAAC VARGAS / NEXTGENRADIO

“We prioritize. It’s okay,” Kaehler said.

Kaehler cares for her animals like they’re her own children. But for this four-legged family, the future is still unclear.

The Kaehlers said they are lucky to have full-time jobs to finance their passion for boarding horses and adopting donkeys, but even they have to consider their expenses moving forward to provide the best care for their animals.

They use an automatic horse waterer that continuously fills up as the animals drink. However, in the summer they supplement it with a 70-gallon waterer.

“Each day, at least 35 gallons have been drunk down. It just gives you an idea of how much water they do need,” Kaehler explained.

Karen Kaehler embraces Jenny, a donkey that came from a cattle farm in Kansas 14 years ago. Kaehler describes Jenny as a “busybody” who always follows her around to make sure everything is under control. Jenny wears socks around her legs to protect her from flies in the summer.

ISAAC VARGAS / NEXTGENRADIO

She describes time spent with her animals as spiritual. She said they have become emotional support animals for a hobby farmer who characterized the last couple of years as “personally challenging,” while holding back tears.

They are her escape from the stresses of everyday life.

“When I meet people who are going through something, I always invite them to have some quiet time with the donkeys,” Kaehler said. “If you like golden retrievers, you’ll pretty much love donkeys because they have that kind of affection for their owners.”

Donkeys in the state of Colorado have a rich history that dates back to the early days of the mining industry. Today, the need for these desert animals has diminished, creating a problem with overpopulation. Climate change could only exacerbate the death toll of wild burros, which are federally protected.

“These are noble beasts who have literally built our country,” Kaehler said, “They deserve our attention…and our love.”

Karen Kaehler and her husband, Brian, talk while watching their horses and donkeys at Chamor Stables in Strasburg, Colorado. Kaehler grew up a self-described “horse girl” in Florida before moving to Colorado in 2001. She got her first donkey in 2003.

ISAAC VARGAS / NEXTGENRADIO